|

|

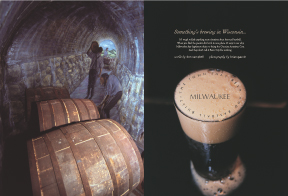

| Milwaukee: The Town That Beer & Baseball Built |

Photos by Brian Gauvin/Gauvin Photography

Photos by Brian Gauvin/Gauvin Photography

Recite the Pledge of Allegiance, sing the national anthem and bake an apple pie and you

still won't find anything more American than beer and baseball.

When you find the passion for both in one place, it's easy to see why Milwaukee lays

legitimate claim to being the Genuine American City. And they don't call it Brew City for

nothing.

Milwaukee was founded on the gleaming copper wort kettles of some of America's best-known

brands of liquid gold, and on the green-diamond exploits of amateur and professional baseball.

Beer - that staff of life, that liquid bread, that nourishing fluid of the working man and

woman -- earned several city fathers-turned-influential brewery men vast fortunes, furthered

their philanthropy and put the town on the map. And the hue and cry of "Play ball!" throughout

the last century and a half on the ballfields of Milwaukee - from corner sandlots to the old

County Stadium to the gleaming new Miller Park, and teams like the Milwaukee Braves and the

Brewers -- helped in no small way establish this All-America city on the placid shores of

Lake Michigan.

ANOTHER ROUND

To borrow a slogan, it was the beer that made Milwaukee famous.

Milwaukee knows a thing or two about beer. It's as though there's been a river of it flowing

through this tidy Midwestern town since it was founded in 1846. Why? There was abundant grain,

clean clear water, and a thirsty contingent of immigrants from beer havens like Germany and

Poland. It was easily shipped from this then-bustling port city to places like Chicago and

St. Louis, and while it can't be proven, Milwuakee brewery sales skyrocketed shortly after

the mysteriously started Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Coincidence?

We all know Milwaukee's beers. They've pervaded our national consciousness, and soothed

parched throats, for nearly a century. Pabst, the granddaddy of Milwaukee beers. Miller,

the Champagne of Bottled Beer, and a thriving corporate citizen with many labels and a huge

new ballpark to its name. Schlitz, Blatz, and even Best, all long since faded from the scene

and absorbed by the American corporate beast.

The tradition of fine beer lives on with the new kids on the dock. Sprecher, Lakefront,

Milwaukee Ale. This is handcrafted beer, brewed in old-school ways in small batches. All

have found favor with Wisconsites. Though Miller thrives, and Pabst (which is owned by

Miller these days) lives on, it's a refreshing trend.

The Frederick Pabst mansion, on Wisconsin Avenue near downtown Milwaukee, is a hub of

Milwaukee brewing history and a fine place to start any tour of the town. Colonel Pabst

brewed his way to beer barondom. Every terra cotta brick of this Flemish Renaissance

masterpiece, every piece of French rococo trim, every gilded armchair was purchased with

the proceeds of Pabst beer.

A steamship cabin boy in his youth, who rose to the rank of storied captain, Pabst became

friends with Phillip Best, who at that time owned the Empire Brewery, the city's largest.

In 1862, he married Best's daughter, in 1864 he bought into the brewery, and by 1866 he

owned it outright.

Pabst was a remarkable and ambitious man. He devised new brewing methods and turned Pabst

beer into a national commodity, eventually owning taverns and hotels around America that

served nothing but his products. He was congenial, approachable and popular, and one time was

asked by both political parties to run for governor of Wisconsin. Though he turned them down

he was active in local politics, and was a devoted patron of the arts, and an avid supporter

of local Milwaukee baseball. Were it not for the Indians, who christened this place Milliocki,

the town may well have been known as Pabst, Wisconsin.

MILLER TIME

Unless, of course, Frederick Miller had something to say about it. There's a trace of Miller's

old Plank Road Brewery, east of downtown proper, with a replica of his house, the cool and

dank storage caverns and a ton of memories. But these days, Miller Brewing is a sprawling

complex of brewhouses, bottling plants, administrative offices and gift shop.

There's no escaping Miller. Owned by Phillip Morris since 1969, it is one of the larger

employers in Milwaukee, with 1200 administrative and 800 brewery staff, brewing up some

1/2-million cases of various beers and malt beverages a day that fly out the door by rail

and semi from 22 loading docks to a grocer's shelf or tavern near you. It now produces

some 45 labels, including Lienenkugel, a regional Wisconsin brewery gobbled up by corporate

expansion, Milwaukee's Best, Red Dog, Henry Weinhard's, Hamm's, Olde English 800 and Mickey's.

Dr. David Ryder is the guru of beer at Miller. His official title is Vice President,

Brewing, Research and Quality Assurance, but that's just a fancy way of saying professional

beer geek. Dr. Ryder has been around the world essentially learning the art of brewing for

the past 25 years. To him, beer is practically a religion.

"Beer is a wonderful product," he says in a lilting British accent. "It was the world's

first nutriceutical product. Drunk in moderation, it's quite good for you, doesn't make you

sick, and provides trace elements and vitamins. Throughout history it's been used as a

tonic. It's a beverage of moderation, and has been fairly socially acceptable. It is,

after all, Miller Time! it's a social beverage, time to get together. We're very proud of

that particularly."

Ryder, who openly admits that he and his staff generally attend twice-daily tastings for

quality assurance purposes, cites Miller's firsts throughout the history of American brewing.

First to patent light stable hops. First to market beer in clear glass bottles. First to

invent what the brewery calls "happy yeast." And the research continues to find new ways

to improve the flavor of beer.

"If you can't have fun in the brewery," Dr. Ryder says with a grin, "you can't have fun

in life."

THE NEW KIDS

People who brew beer are a breed apart. That's proven in the cadre of small breweries in

Milwaukee that are bubbling up some fine beer. An easy way to make a tour of Milwaukee's

boutique brewers is aboard the River Queen. Entrepreneur and restaurateur Russ Davis operates

the weekly runs up and down the Milwaukee River, with stops at the Lakefront Brewery, Rock

Bottom (a national chain, but a tasty stop nonetheless), and the Milwaukee Alehouse. "We

started as a river taxi three years ago," he says. "The brewery tours, which we run on

Saturdays and Sundays, have been pretty successful. It wouldn't work everywhere in the U.S.,

but it works here." Tours run June through October, when the weather's hospitable.

Lakefront, the first stop, is run by two brothers, Jim and Russ Klisch, who've been brewing

beer for 15 years. Their grandfather drove a truck for Schlitz. Russ is the quiet one. Jim

is a nut and the one who runs the tours. His patter is quick, practiced and hilarious as he

guides visitors around the Lakefront brewery building. It's set in an ancient power plant

in the old part of town, along the Milwaukee River.

"The brewing heritage in the city was on the decline," Jim says. "Schlitz was sold to Stroh's,

Miller was bought by Phillip Morris. We became aware of the whole microbrewery movement as

it was developing on the West Coast. We thought we'd try it here. You know how it is, as a

home brewer. You're stirring the mash on the kitchen stove, you smell the fragrance, and you

have visions of grandeur that you could start your own brewery. This is a homebrew operation

gone crazy."

But they've succeeded. They've gone from 56 barrels of beer that they hand-carted to the

four local taverns, to 4,400 barrels and shipping as far away as Chicago. But for perspective,

says Jim, "Anhauser-Busch will spill more beer in one shift than we're going to make all year."

The brothers Klisch brew a variety of lagers and ales, including White, Cream City Pale Ale,

Riverwest Stein Beer, Eastside Dark and Red Lager - somel named after Milwaukee neighborhoods

- plus the occasional seasonal beer. The brewery is not open to the public every day, but

tours are offered frequently, and the beer is available all over the city.

Rock Bottom is a pleasant stop, if only for the short journey up the river from Lakefront.

During the brewery tour, Davis explains how the Milwaukee riverfront is developing, with its

own San Antonio-like RiverWalk emerging, boat docks and even art parked along the water.

At the Milwaukee Ale House, located where the Milwaukee and Menomenee rivers come together,

in Milwaukee's historic Third Ward, one is treated to tasty handcrafted beer, bar food that's

a notch or two above the norm, the chance to hear live blues and rock and roll on weekend

nights. On this particular day, the pub is crawling with official men in black with earpieces

in their ears. The king and queen of Norway are in the house. Though our little tour hoped

for the chance to quaff a brew with royalty, it was not to be. Security is tight.

Owner Jim McCabe walks us through the small brewery as we sample the goods. Above the tanks

is a plaque: "Blessed is the mother who gives birth to a brewer," uttered by brewer Jim Olen's

mother, McCabe says. "We all have the mother's of brewers to thank for great beer."

They love beer here. Louie's Demise, a house favorite, got its name from a legendary bar

fight, That kind of ambience pervades the place, though now it's more known for the blues

music than beer-fueled bar fights. "We're most like Jim and Russ, in that we were home brewers

and wanted to own a brewery. Brew City is a great place to brew beer," McCabe says. "But

we're like a gnat on an elephant's behind. Marketshare wise, craft beer is hovering right at

5 and 6 percent of every beer consumed. That's small."

A stop not on the River Queen tour, but one that must be made, is at the Sprecher Brewery.

Randy Sprecher is brewing some of the city's finest beer, and a successful line of sodas,

in his modest, historic refurbished brewery north of the downtown. Brewing since 1985,

Sprecher was stationed in Germany and fell in love with beer. He returned home to Eugene,

Oregon, and began brewing his own. He discovered he had a knack for it and pursued his passion

by earning a degree at the University of California at Davis, and got a degree in fermentation

science. He was recruited by Pabst in Milwaukee, and never left.

Unhappy with the corporate structure at Pabst, he struck out on his own with Sprecher Brewery,

which now draws 15,000 people a year for brewery visits, and stocks Wisconsin with an

assortment of well-crafted bottles and kegs. By all accounts Sprecher is an inspired master

brewer. He's been known to dream up recipes off the top of his head.

"It's hard to get rich making beer," he says. "I've been doing it for over 30 years, since

I got back from Germany in '69. I knew by '74 I was going to get involved with this. A lot's

changed in 30 years. I've had my moments of doubt, but once we got rolling into our third

year we were doing pretty well, we were profitable. But in Wisconsin, it's hard to grow

the business. We'll see what happens. I just as soon sell more beer in China, where the

market is just monstrous."

HOME RUN

Beer, baseball and bratwurst - the holy trinity - go together like Tinker-to-Evans-to-Chance.

This is a baseball town, and it's easy to find all three, especially at Miller Park.

Milwaukee Brewers spokesman Jon Greenberg rattles off the four significant ballparks in

the city's history: Miller Park, County Stadium (which was torn down to make way for Miller

Park), Borchard Park and the Lloyd Street Field from the turn of the century. He tells me

that the city's first team arrived in the 1870s as the American Association Milwaukee Brewers.

The Brewers lived on in the original American League in 1901. They left town to become the

Baltimore Orioles.

A minor league team filled the gap (again called the Brewers) before the Boston Braves

relocated, to become the Milwaukee Braves from 1953 through '65, with a World Series

appearance in '57. In 1970, the Seattle Pilots are sold to Milwaukee and the Brewers are

reborn, with another World Series appearance in 1982, in a contest that became known as

the Suds Series, as the team faced the St. Louis Cardinals.

There's a vibrant buzz on game day around Miller Park. For as long as there has been

baseball, there have been tailgate parties and here the tailgater is ritual and fundamental.

Fresh-faced kids play ball - catch, home-run derby, pickle, you name it - until there are

too many cars. A thin haze blankets the lot. Weber has apparently cornered the market here

on portable grills where everything from chicken to burgers to mouthwatering bratwursts is

grilled to a tantalizing turn. And, of course, there are ice-cold Miller Beer, Pabst and

Lienenkugel in big ice chests. Fans arrive hours before game time to socialize in a

fellowship that might well be depicted in a Norman Rockwell painting. This, folks, is

America.

Then it's game time. The only thing better than a day at the beach is a day at the ballpark.

Located very near Miller Brewing, Miller Park is 41,900 seats of baseball grandeur, and

home to not only the National League Milwaukee Brewers, but to the 2002 MLB All-Star Game,

held last July.

The park has a fan-like, 12,000-panel, seven-ton retractable roof (spring in Milwaukee

can be iffy at best, with plenty of 50-degree days), four spectacular decks, and several

corners of serious baseball memorabilia that will jaw-drop any serious baseball fan. Babe

Ruth's bat. Carl Yastremski's jersey. Honorees from the Negro League. Pictures of the Wisconsin

women who played in the Milwaukee Chicks, part of the Girls Professional Baseball League,

immortalized in the Tom Hanks-Geena Davis-Madonna movie "A League of Their Own."

This is the team that Robin Yount, Hank Aaron, Paul Molitor and Rollie Fingers built.

All are Hall of Famers, all immortalized in a Walk of Fame at Miller Park. The place oozes

baseball from every pore.

Armed with a beer and bratwurst, featuring the stadium's Secret Sauce, it's easy to sit

back, sip and enjoy. Sunlight streams in through the panes of glass, redolent of an old

train station. Brewer Matt Stain spanks a two-run homer. Two concussive cannon shots

rattle the stadium, and Bernie Brewer takes his slide. The Brewers ultimately lose,

but it hardly matters. Beer and baseball in a town like Milwaukee. It's a pretty good

rendition of heaven.

Don Campbell is a frequent contributor to World Traveler magazine.

| |

|